Let It Flow

Algorithmic art has made the beauty of code visible to non-coders. But perhaps no foundational technique is more recognizable (or misunderstood) than the humble flow field.

Apr 10 - May 1

One of the wonderful things about generative art is how it’s introduced so many people to the beautiful nature of code. Modern life is governed by unseen algorithms beyond our control. But generative art can take an algorithm and make it visible and tangible, imbuing it with emotion.

Encountering generative art for the first time, viewers primarily engage with the outputs on an aesthetic level. But as they learn more about generative systems, they start to recognize recurring technical methods used across multiple projects. The medium reveals to non-coders core concepts around randomness and emergence, as well as creative coding techniques ranging from particle systems to recursion and cellular automata. And perhaps no method is more recognizable today than the flow field: the focus for the Dawn Contemporary gallery’s latest show, Let It Flow, releasing on Alba.

"Flow fields…are ideal when I have a need to add organic movement, dynamism, or rhythm into a piece."

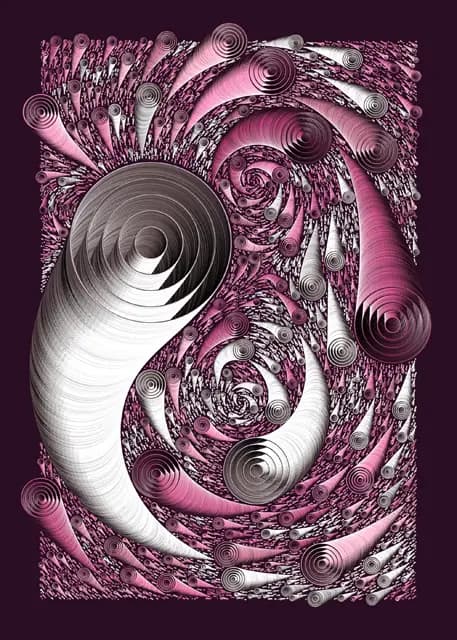

Resting Place For Wild Pigeons

Juhani Halkomäki

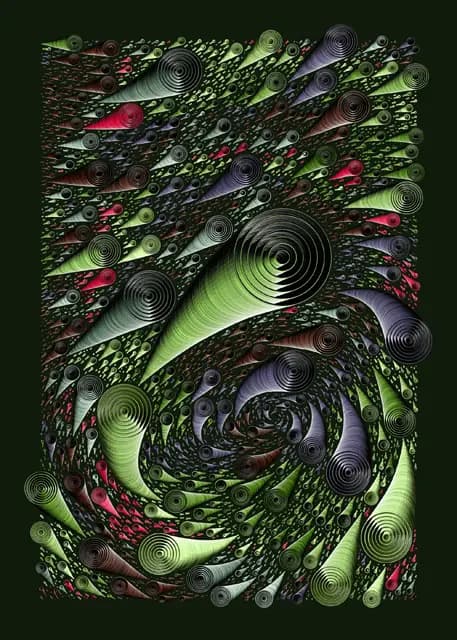

Finding the Way

White Koala

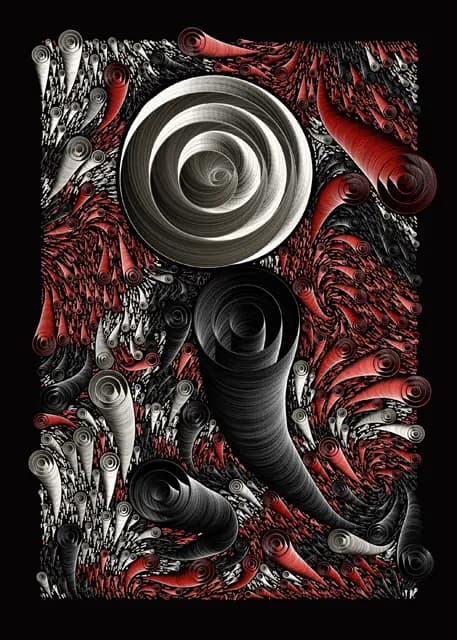

Noisia

nico23

A foundational technique made iconic to many by Tyler Hobbs’s Fidenza, flow fields are like dropping a beach ball into the middle of the ocean. You can trace the object’s path from one section to the next; in some places the current causes the ball to change direction, while in others it speeds up or slows down. Looking at the open water, the surface appears to be a mass of haphazard waves, but from a bird’s-eye view, you start to see in the currents the underlying pattern of a system at work.

Flow fields echo this effect. The canvas is divided into sections, like quadrants on a map, each with its own direction and speed (in math, we might call these the angle and magnitude of a vector). When an artist places an object on their canvas — from a simple geometric shape to complex brushstrokes — it flows across this invisible grid, often leaving a trail in its wake. It’s a powerful tool for introducing the organic qualities of motion as found in nature into the digital realm.

"I’ve always been fascinated by the algorithmic beauty of nature."

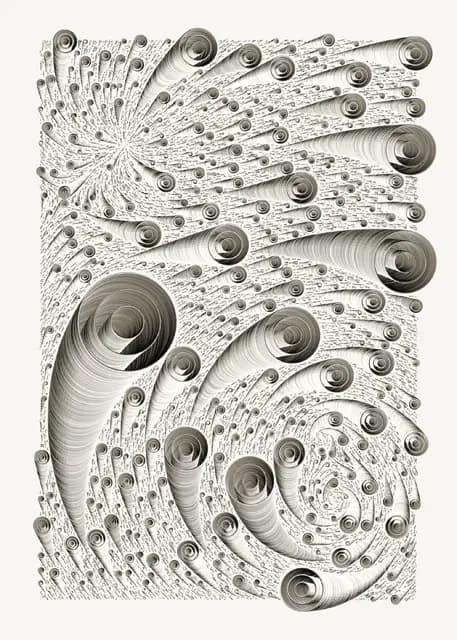

Evanescencia by Leonardo Solaas

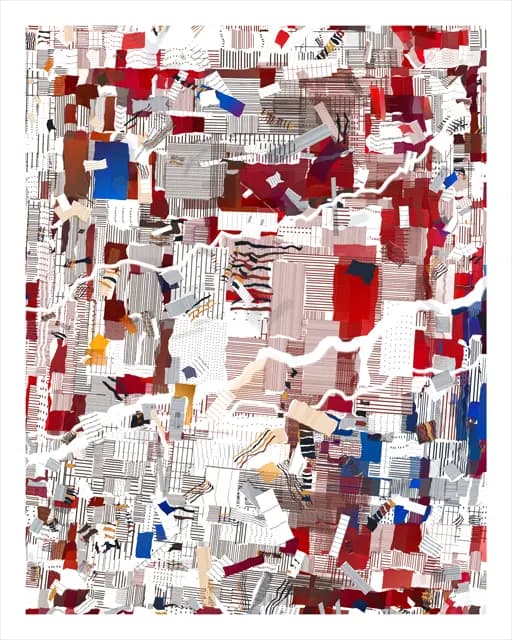

Finding the Way by White Koala

Yet, despite flow fields being a core building block in a generative artist’s toolbox, when new projects use this technique today, artists often get comments calling the work basic. Or, the work is accused of being “another Fidenza knockoff.”

Ironically, if every piece that uses a flow field is seen as derivative of earlier works, then Tyler Hobbs might be the worst offender. As he wrote in an early 2020 essay published over a year before the release of Fidenza, “[Flow fields] are one of the main tools I've used in my own generative art over the last few years, and I find myself going back to them over and over again. It's entirely possible that I've used them in more programs than any other person alive.” So Fidenzas belong to a long line of projects in Hobbs’s oeuvre that rely on this foundational technique.

And that’s how it should be. It can take an artist years of mining the same rich terrain before they truly strike gold — and Hobbs’s approach is evidence that flow fields are rich terrain indeed. So instead of telling artists that they should stop using flow fields, we should encourage them to push their work further, to dig deeper with the techniques that interest them most.

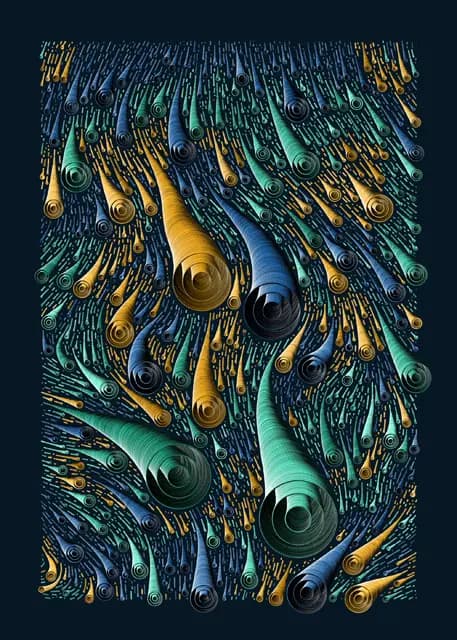

“This project really took off when the lines started to form new shapes, first by transforming into droplets, and then, as I continued experimenting, the droplets extruded into the third dimension…I was just following my intuition.”

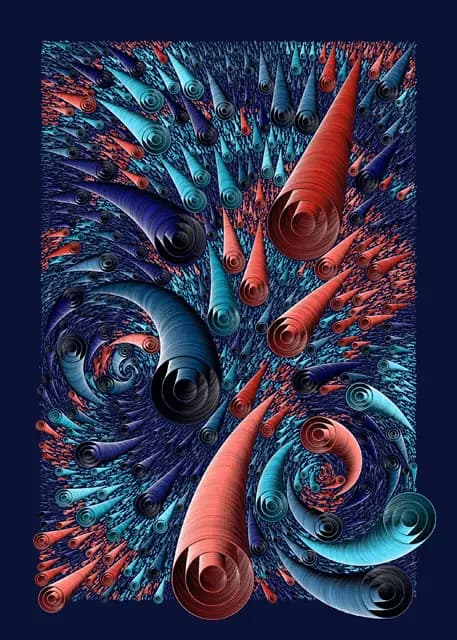

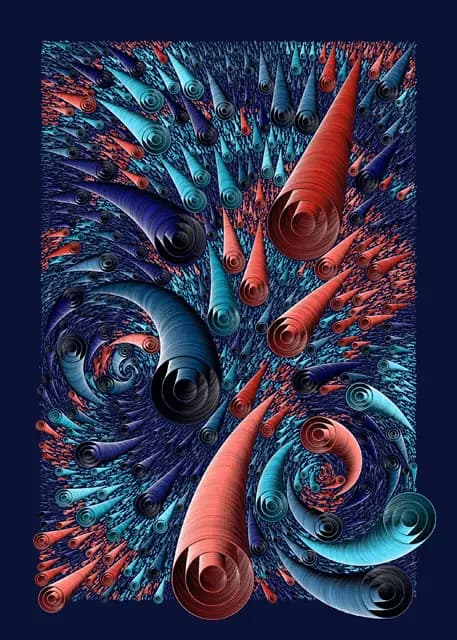

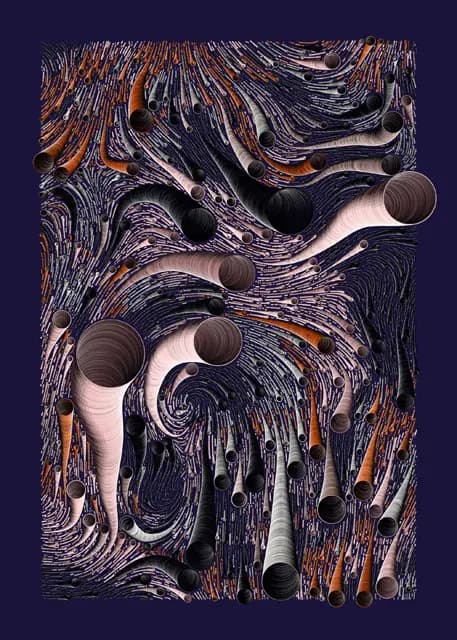

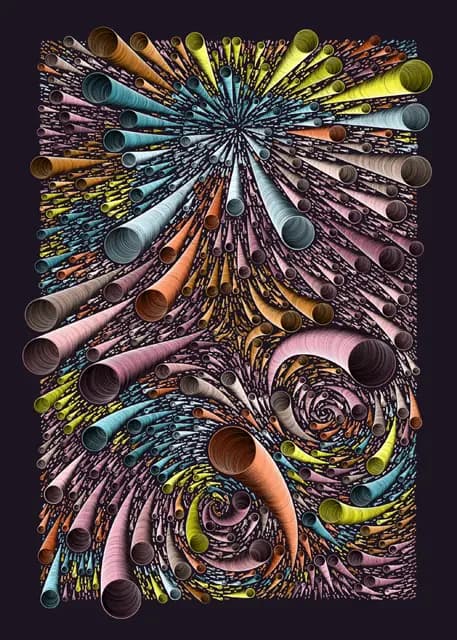

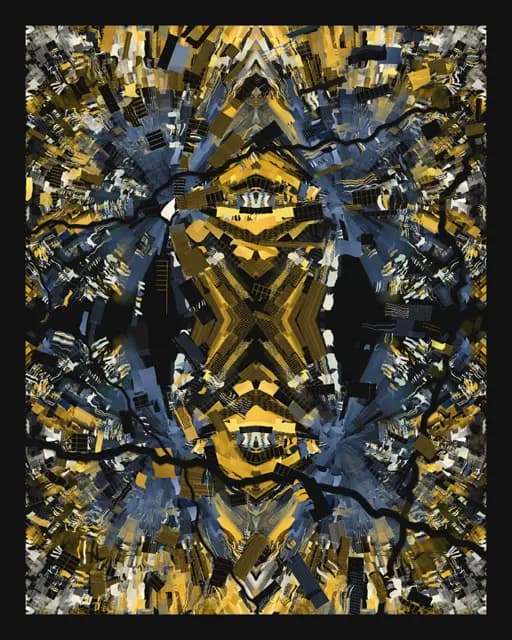

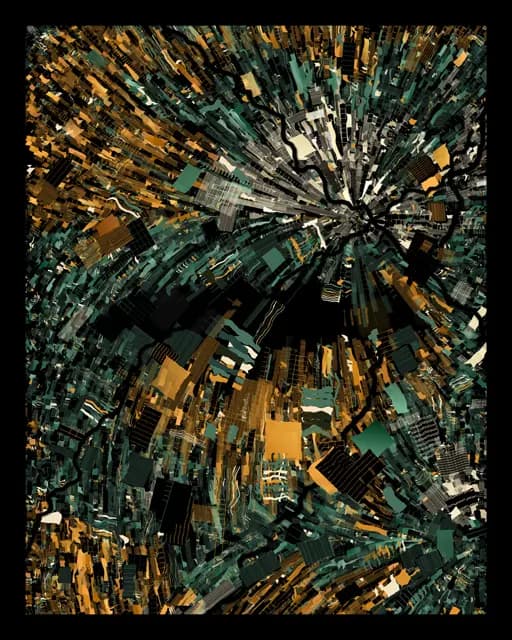

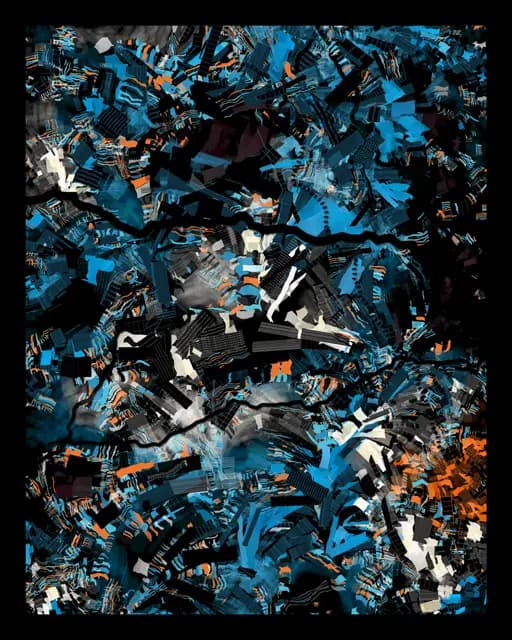

Resting Place For Wild Pigeons by Juhani Halkomäki

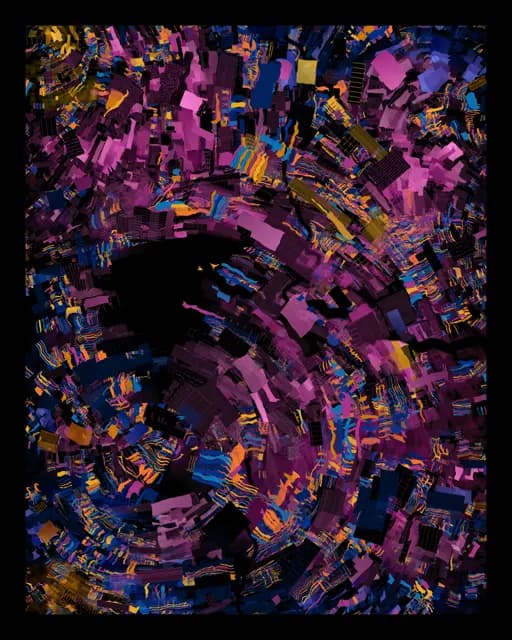

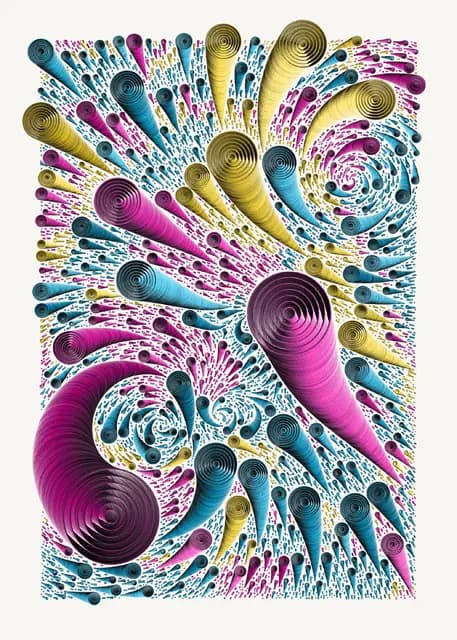

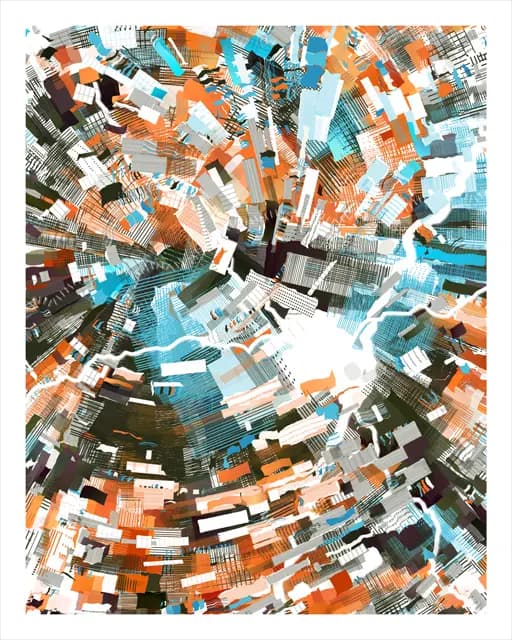

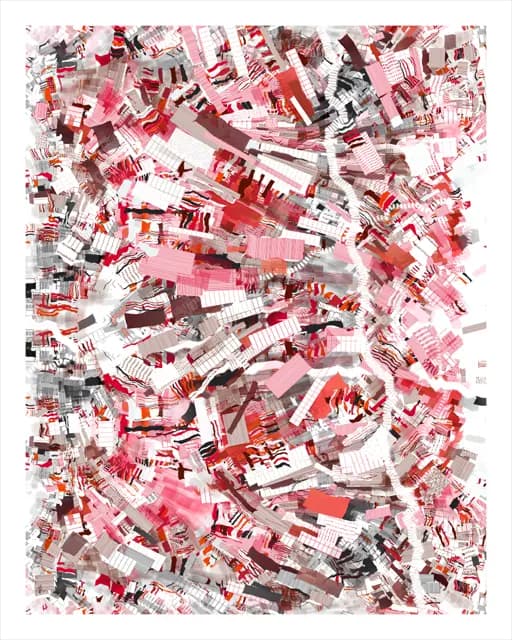

NOISIA by nico23

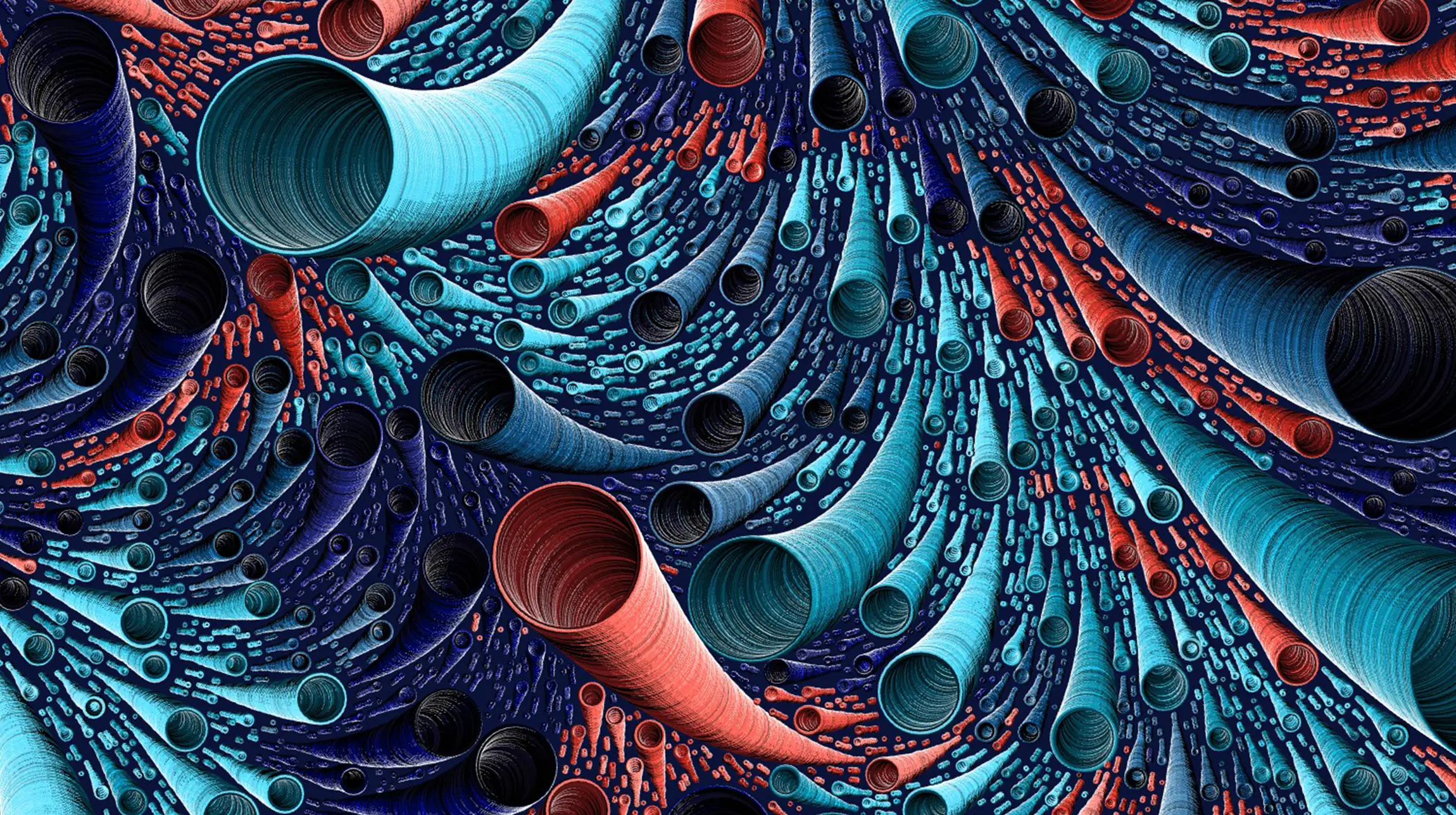

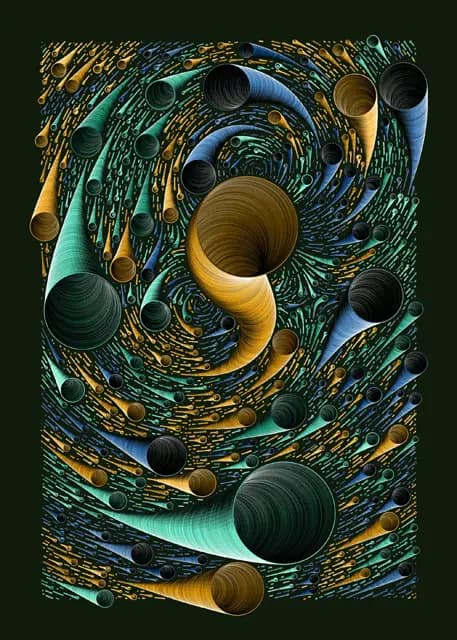

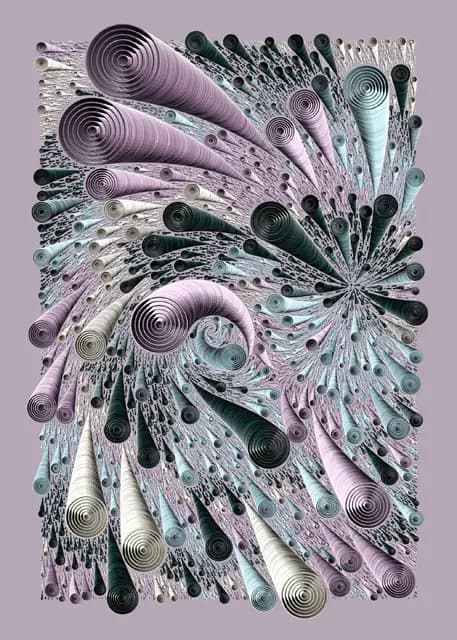

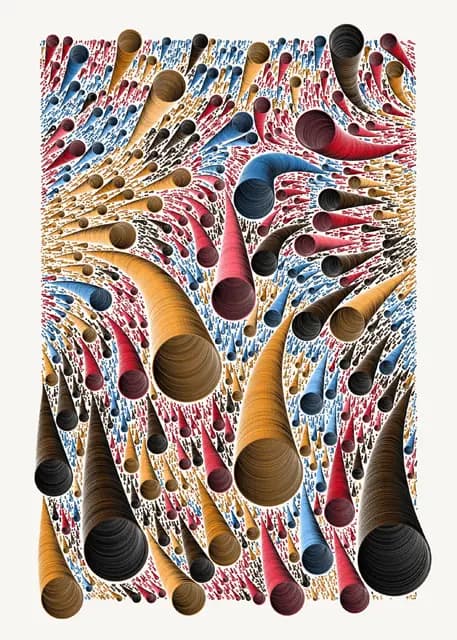

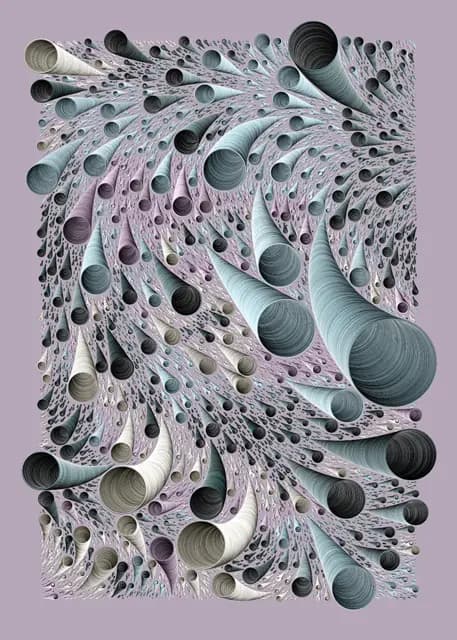

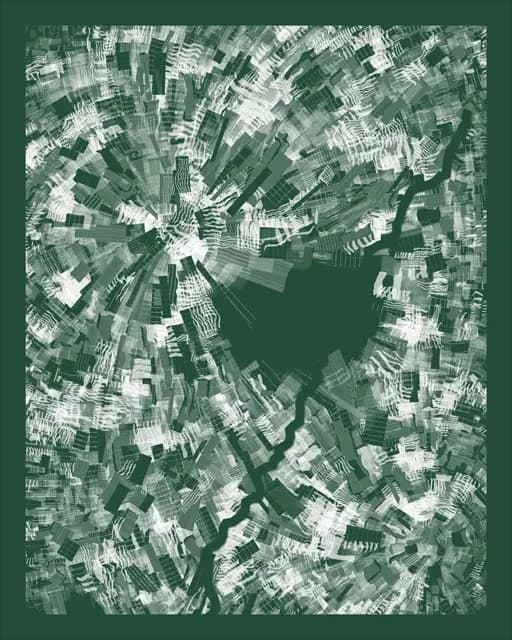

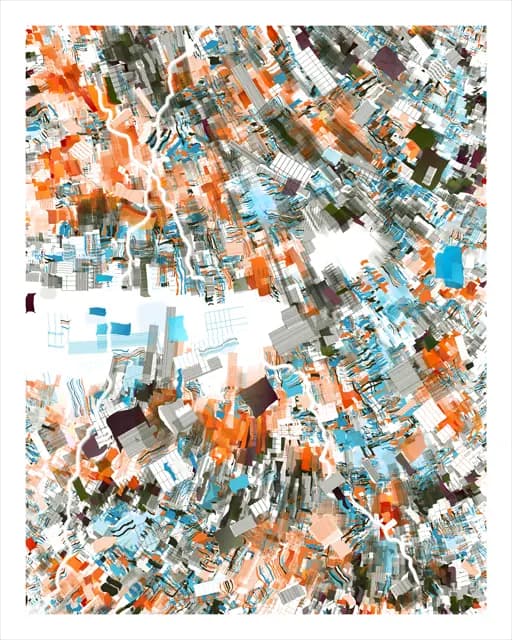

The projects in Let It Flow are our way of reclaiming flow fields back from the naysayers and negative comments. As Dawn Contemporary’s fifth group show, Let It Flow is a celebration of the vast variety of approaches artists can take when they layer a flow field into their work, from the haunting, hazy flowers of Evanescencia by Leonardo Solaas to the cosmic wormholes swimming through Resting Place for Wild Pigeons by Juhani Halkomäki. The spare, swirling shapes in Noisia by nico23 stand in stark contrast to the maximalist, quilted patterns in Finding the Way by White Koala. The diversity of styles throughout Let It Flow points to a breadth of possibility when flow fields are layered with other creative coding techniques, and it affirms a rich vitality, to which artists can return again and again.

“By experimenting with different levels of detail, from a unidirectional flow to a rapidly changing arrangement of paths, it's possible to discover completely new and unexpected visuals far from the initial concept.”

Telling artists they shouldn’t use flow fields because of one famous project is like telling a chef they can’t use basil in a dish because you once had caprese. There are so many different ways to use basil in cooking, and the same goes for flow fields. As in any good dish, the trick is to layer multiple flavors together — or, in this case, coding techniques — until they merge into something new and unexpected. You can still taste the basil, or sense the flow field, but the pleasure you have in each bite means it doesn’t matter.

NOISIA by nico23

Finding the Way by White Koala

Furthermore, when collectors dislike a flow field piece, the issue they’re responding to isn’t the flow field. It’s the one-note execution. It’s the student exercise cribbed from YouTube, failing to push far enough. It’s the pattern, not the tool. Artists should still get to use the tool. As Hobbs explained in his same 2020 essay, “Flow fields are…something that many programmers reach for…when they first get into creating algorithmic artwork, but few take the time to polish their use and explore the crazy variety of ways they can be used.

“I make a distinction between the technique of the flow field in genart and the aesthetic subgenre of the flow field. From a technical standpoint, a flow field is very useful in many algorithms.”

The way an artist assigns and warps the initial movement and direction of the vectors in their flow field determines the patterns that appear in the work, whether they’re smooth or jagged, organized or chaotic, fresh or familiar. As a result, the real culprit for the visual predictability that collectors often complain about stems from how the vector values are initialized.

Unfortunately, too many artists turn to noise (particularly Perlin noise) at this crucial step. The results are homogenous and familiar, which betrays the vast variety of possibilities latent within flow fields. Hobbs knows this. In his essay, he encourages artists to “come up with your own distortion techniques” and to avoid “relying on Perlin noise, simply because it’s so overdone.” And that was in early 2020, before the generative art boom of the last few years!

Resting Place For Wild Pigeons by Juhani Halkomäki

Evanescencia by Leonardo Solaas

Rather than relying on noise, artists interested in flow fields should, as Hobbs observed, find their “own distortion techniques” for manipulating the way objects flow between different vectors: play with various rule sets, design their own seeding algorithms, explore non-continuous flow patterns, overlap paths or entire fields, introduce attractors and repellers, set various trigger states, or change the cadence of the grid — does it even need to be a grid in the first place?

“The particular twist I put on this technique from the beginning was to use an actual image as a force field, instead of noise functions…I’m interested in the endless styles and effects that can be obtained just by tweaking the formulas.”

The field is wide open to discover new flavors and ways of layering multiple techniques together into something new – and that’s what the selection of works featured in Let It Flow seek to explore. This show is about taking back this much maligned and misunderstood technique from those who’ve been quick to dismiss all other flow field pieces in the wake of Fidenza’s success. If Hobbs could find years of material worth exploring in the humble flow field, then so can other artists. It’s all about digging deeper to see what rich veins are out there. Because it can all look the same, until it doesn’t.

Resting Place For Wild Pigeons

Finding the Way

Noisia